The National Security and Intelligence Review Agency (NSIRA) tabled its annual report on October 30, 2023. NSIRA is responsible for conducting national security reviews of Canadian federal agencies, and its annual report summarises activities that have been undertaken in 2022. The report also discusses new policies and capacities concerning its review activities.

In this post, I summarise and discuss many of the central items in the annual report. This includes the Agency’s approach to developing themes and categorising recommendations, aspects of particular the reviews, how NSIRA’s technology directorate is developing, the ways in which NSIRA is maturing how it measures engagements with reviewed agencies and associated confidence ratings, and its international engagements.

Significantly, this annual report includes several explicit calls for legislative review as pertain to complaints investigations. It is, also, possible that the Agency may be building an evidence-based argument for why law reform may be needed to ensure that NSIRA can obtain adequate access to information or materials to conduct reviews of some government agencies.

Themes and Categorisation of Recommendations

NSIRA has been developing and issuing recommendations to government institutions for multiple years. The result is that the Agency can begin to categorise the kinds of recommendations that it is issuing. Categorisation is helpful because it can start to reveal trends within and across reviewed institutions and, then, enable those institutions to better focus their efforts to update organisational practices. Moveover, with this information NSIRA may generally be able to monitor for substantive changes in common problem areas both within and across reviewed agencies.

The following table re-creates the categorisation descriptions in NSIRA’s annual report(see: page 3).

| Theme | Topics |

|---|---|

| Governance |

|

| Propriety |

|

| Information management and sharing |

|

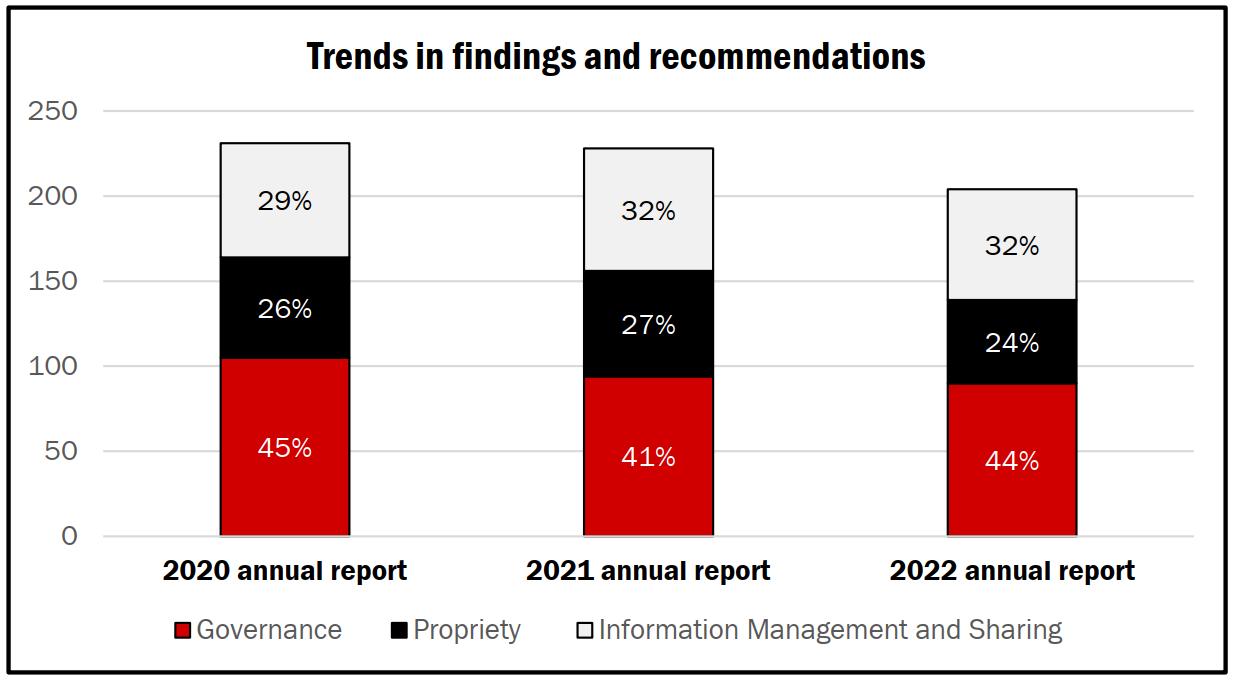

This tripartite division lets NSIRA categorise all of the different recommendations it has made in its 2020, 2021, and 2022 annual reports, which has the effect of showcasing trends over the years. I have republished NSIRA’s chart denoting these trends, below.

Analysis of Themes and Categorisation of Recommendations

I can’t immediately think of items that do not fit in the categories that NSIRA has developed, though it will be interesting to observe over time whether this categorisation will continue to capture all possible types of recommendations. Further, with this categorisation schema now in hand, will this affect the crafting of recommendations so that they clearly ‘fit’ within each of these categories? Will single recommendations sometimes fit within multiple categories? Or is it possible that additional categories may be developed based on future recommendations?

I can see the strong utility of this, generally, for organisations — be they government or non-government — to track the kinds of recommendations they are making. It could both assist with internal tracking and governance measures while, also, focusing in on the core classes of issues that are being found within and across organisations that are under review, or otherwise subject to external examinational or critique.

Reviews

The reviews section of NSIRA’s annual report summarises the reviews that the Agency has undertaken over the past year, with those full reports generally available on NSIRA’s website.1

Reviews of CSIS Activities

NSIRA provides a range of different statistics concerning CSIS’ activities, including those concerning:

- Warrants that are sought

- Threat Reduction Measures (TRMs)

- CSIS targets

- Dataset evaluation and retention

- Justified commissions of activities that otherwise would involve committing or directing the committing of unlawful acts

- Compliance incidents

In what follows I identify noteworthy aspects of the statistics and associated narratives provided. First, warrants sought by CSIS may be used “to intercept communications, enter a location, or obtain information, records or documents. Each individual warrant application could include multiple individuals or request the use of multiple intrusive powers.” It is worth highlighting that NSIRA has explicitly stated in footnote 15 that:

A number of warrants issued during this period reflected the development of innovative new authorities and collection techniques, which required close collaboration between collectors, technology operators, policy analysts and legal counsel.2

Warranted authorisations were granted under section 12,3 16,4 and 21 5 of the CSIS Act as well as two authorisations under section 11.13 6. The total number of warrants that have been sought and approved are in line with previous years’ statistics, standing at 28, with 6 being new, 14 being replacements, and 8 being supplemental.

TRMs can be sought and exercised without requiring judicial authorisation, so long as the activity in question does not “limit a right or freedom protected by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms or would otherwise be contrary to Canadian law”. Warrants are required when an activity would conflict with Charter rights or Canadian law. The number of authorisation sought (16) was about in the middle of the lower (10) and upper (24) bounds of requested authorisations in previous years, and executed TRMs (12) is similarly in the middle of the lower (8) and upper (19) bounds of past years’ statistics.

CSIS targets have declined over the past 5 years, moving from 430 targets in 2018 to 340 in 2022. However, this number can be misleading on the basis that a target could be for an individual or a group composing many people.

CSIS continues to notify NSIRA about judicial authorisations or ministerial authorisations to collect Canadian or foreign datasets, in excess of what the Service is required to do under the law. Generally, the statistics show that evaluated datasets tend to be retained and neither the Federal Court, Minister, or Intelligence Commissioner have denied CSIS the ability to retain evaluated datasets.

There have been considerable increases in the number of authorizations to CSIS personnel to undertake activities that involve “committing an act or omission themselves (commissions by employees)” or directing “another person to commit an act or omission (directions to commit) as a part of their duties and functions.” Relatedly, there have also been more commissions/directions to commit that have been recorded. Statistics are denoted in the below table, which was produced by NSIRA.

Finally, the compliance information provided by NSIRA shows a growing breakdown of the ways in which CSIS activates can found to be non-compliant with either Canadian law, the Charter, warrant conditions, or CSIS governance practices.

Analysis of CSIS Activities

A few things clearly drew my attention.

- It is unclear what the new warranted authorities or collection activities have involved, but the listing of parties involved in developing these suggest that there may be a notable expansion in CSIS capabilities.

- It might be helpful in future reports to have a footnote explaining the difference between new, replacement, and supplemental warrants. The last item, in particular, is a term that I’m not familiar with, which suggests that many others reading these reports who are not national security insiders or legal experts may have similar questions.

- That no judicially supervised TRMs have been undertaken is notable and suggests that these measures may not yet have risen to concerns raised by some civil society and other actors. In particular, past concerns have focused on how how these techniques could affect residents of Canada and their Charter rights.

- We still lack clear an understanding of what, precisely, is being evaluated or retained by CSIS when it collects datasets and subsequently analyses them. This remains a significant blindspot and prevents the public or legislators from clearly understanding what, exactly, CSIS can do (or is doing) with retained datasets.

- The justifications framework makes clear that more and more activities are being undertaken which would, otherwise, be unlawful. It is an open question whether these activities may impede the ability of federal law enforcement, or other parties, to use the Criminal Code (or other legislation) to take action against individuals or groups in Canada who have been targeted by CSIS. Specifically, what (if any) relationship is there between these justified activities undertaken by CSIS and the One Vision 3.0 framework between the RCMP and CSIS?

Communications Security Establishment

NSIRA undertook two reviews of CSE activities, including about Active Cyber Operations (ACO) and Defensive Cyber Operations (DCO), and of an undisclosed foreign intelligence activity.

NSIRA found that “ACOs and DCOs that CSE planned or conducted during the period of review were lawful and noted improvements in GAC’s assessments for foreign policy risk and international law” and as well as that “CSE developed and improved its processes for the planning and conduct of ACOs and DCOs in a way that reflected some of NSIRA’s observations from the governance review.” However, “NSIRA faced significant challenges in accessing CSE information on this review. These access challenges had a negative impact on the review. As a result, NSIRA could not be confident in the completeness of information provided by CSE.“7

The CSE collection activity is not described in any detail, though NSIRA “identified several instances where the program’s activities were not adequately captured within CSE’s applications for certain ministerial authorizations.”

NSIRA has had challenges with its reviews of CSE’s operations since the Agency’s establishment. In 2022, this led to NSIRA’s Chair meeting with the Minister of National Defence “to discuss ongoing issues and challenges related to NSIRA reviews of CSE activities.”

The NSIRA annual report includes an extensive set of statistics about the CSE’s activities. To begin, there has been an additional cybersecurity as well as active cyber operations authorisation in 2022 versus 2021, with the effect that there are now:

- 3 foreign intelligence authorisations

- 3 cybersecurity — federal and non-federal — authorisations

- 1 DCO authorisation

- 3 ACO authorisations

We can expect that at least some of these may be linked to the Canadian government’s (and CSE’s) efforts to help Ukraine in its fight against Russia’s illegal war of aggression. However, the general breadth of Ministerial Authorisations are such that any new ones will cover off large categories of activities which could be undertaken in a variety of situations or locations.

My colleague, Bill Robinson, may be pleased to see that CSE is authorising NSIRA to identify the number of reports CSE is releasing (3,185 in 2022), to the number of agencies/departments (26 in 2022), and the number of clients within departments/agencies (1,761 in 2022). He will likely be less pleased to see (as am I) that CSE refuses to release statistics concerning:

- The regularity at which information relating to a Canadian or a person in Canada, or “Canadian-collected information” is included in CSE’s end-product reporting

- The regularity at which Canadian identifying information (CII) is suppressed in CSE foreign intelligence or cyber security reporting

- The number of DCOs or ACOs which were approved, and carried out, in 2022

The regularity at which CII information was released, however, was provided for Government of Canada requests (657) and Five Eyes requests (62). There was an aggregate decrease from 831 requests in 2021 to 719 requests in 2022, with CSE denying 65 of the 2022 requests and 51 of the requests still being processed.

There were more privacy incidents registered by CSE itself (114 in 2022 versus 96 in 2021) and a reduction in second-party incidents (23 in 2022 versus 33 in 2021). No specific information about the nature of the incidents are provided.

There was a large number of cyber incidents that were opened by the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security. This included 1,070 affecting federal institutions and 1,575 affecting critical infrastructure.

While not as detailed as past work by Canadian reporters, which once identified how many times CSE provided assistance to specific federal partners, NSIRA’s 2022 annual report does continue to disclose how frequently CSE receives requests for assistance. In 2022 it received 62 requests (up from 35 in 2021), with 1 cancelled and 2 denied, resulting in 59 being approved.

Analysis of CSE Activities

There are numerous things that are of note in the section of CSE.

- Despite having reviewed ACO and DCO activities, NSIRA was unable to be confident of the information it had been provided when conducting the review. Put differently, we should take the outputs of the review with a grain of salt, and this matters both on a governance level as well as because ACOs and DCOs have the potential to be extremely impactful to individuals’ Charter or human rights.8

- Issues between NSIRA and CSE have risen to the level that the Chair of NSIRA and Minister of National Defence are meeting. This is suggestive that issues could not be resolved at the senior staff level despite years of effort to do so. Escalating this to the Minister is about as high-level a complaint or concern that NSIRA can raise within the government hierarchy.

- A mainline privacy concern is how frequently CII is being collected and, subsequently, included in reporting. That CSE continues to refuse to provide statistics on how often it is being suppressed impedes the public’s and politicians’ abilities to understand how much ‘incidental’ collection of CII occurs in the course of the CSE’s activities. A similar complaint can be made concerning CSE’s refusal to release statistics about the regularity at which information related to a Canadian or person in Canada, or “Canadian-collected information” is included in end-product reporting. This issue has even greater salience given that Bill C-26, which addresses critical infrastructure and cybersecurity, is currently at Committee. If passed into law, even more CII or information related to Canadian persons could be obtained by CSE.

- It is unclear whether critical infrastructure incidents opened with the Cyber Centre included just federally regulated institutions or all critical infrastructure providers (including those under provincial jurisdiction). The effect is to impair an understanding of how much work CSE is undertaking on behalf of provinces (or to support provinces in protecting infrastructure) .

- There has been an explosion in how frequently CSE is providing assistance to other federal partners, but it is unclear who specifically is receiving the assistance or to what effect. While the expansion may be linked to the war between Ukraine and Russia, there may be other factors at play which are hidden from the reader due to how NSIRA is permitted to disclose information in its annual report.

Other Departments

NSIRA also conducted reviews of the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces (DND/CAF), Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA), and mandated annual reviews under the Security of Canada Information Disclosure Act (SCIDA) and Avoiding Complicity in Mistreatment by Foreign Entities Act (ACA). Key points include:

- The DND/CAF review saw NSIRA conclude that DND/CAF’s human source handling actives may be being undertaken in ways that are, in NSIRA’s opinion, potentially unlawful. The Minister disagreed, with NSIRA believing that the Minister’s conclusion was a result of applying an inappropriately narrow interpretation of the facts and the law. Further work will continue on this file.

- CBSA’s air passenger targeting review found areas needing improvement, including surrounding documentation practices, and demonstrating adequate justification for its selection of indicators as signals for increased risk.

- GAC was found to need to improve on its disclosure policies under SCIDA, on the basis that GAC “did not meet the two-part threshold requirements of the SCIDA before disclosing the information, which was not compliant with the SCIDA.”

- The definition of “significant risk” related to avoiding complicity in mistreatment by foreign entities does not exist in legislation, which continues to create challenges. NSIRA is calling for this to be addressed in future legislative reform. Moreover, neither the CBSA or Public Safety Canada have fully implemented a framework under the ACA.

- NSIRA has moved to begin closing certain ongoing work or not ultimately produce a final report to a Minister. Other work–including a NSIRA review of how the RCMP handles encryption in the interception of privacy communications in national security criminal investigations–has been deconflicted, given the activities of other review and oversight bodies such as the National Security and Intelligence Committee Of Parliamentarians (NSICOP).

Analysis of Other Departments

- This is not the first time that the activities undertaken by DND/CAF have been subject to critique, such as NSIRA’s assessment of the Canadian Forces National Counter-Intelligence Unit. NSIRA’s ability to examine some of these activities continues to showcase the importance of having a review agency that can comprehensively undertake review across all national security bodies. Moreover, that it is flagging review areas (e.g., the 2020 annual report noted that additional reviews had been initiated/planned, including on DND/CAF’s HUMINT capabilities) and following through speaks well to NSIRA’s ability to meet its commitments.

- There are real risks to individuals when agencies inadequately comply with the ACA. As I have written previously, without adequate frameworks there is a concern that “some agencies will continue to obtain information from, or disclose it to, foreign states which are known to either use information to facilitate abuses, or that use torture or other mistreatment to obtain the information that is sent to Canadian agencies. Which agencies continue to support information sharing with these kinds or states, and their rationales for doing so, should be on the record so that they and the government more broadly can be held accountable for such decision making.”

- It’s worth highlighting that NSIRA is calling for legislative reform to create the definition of “significant risk” concerning the ACA.

- Decisions to close certain reviews–or at least not issue a report to a relevant Minister–reveals a growing maturity within NSIRA as it develops policies and procedures on how to advance its work. I am curious as to whether a decision to not issue a report to a Minister may, still, result in functional improvements in how government agencies undertake select national security activities. Further, the NSICOP report on the RCMP’s handling of encryption will be important to read once it is published given the longstanding debate in Canada over encryption and encryption policies.

Technology Directorate

NSIRA continues to build up its internal technical capabilites, with its team now including engineers, computer scientists, technologists and technology review professionals. The mandate of the Directorate is expansive, and includes:

- Lead the review of Information Technology (IT) systems and capabilities

- Assess a reviewed entity’s IT compliance with applicable laws, ministerial direction and policy

- Conduct independent technical investigations

- Recommend IT system and data safeguards to minimize the risk of legal non-compliance

- Produce reports explaining and interpreting technical subjects

- Lead the integration of technology themes into yearly NSIRA review plans

- Leverage external expertise in the understanding and assessment of IT risks

- Support assigned NSIRA members in the investigation of complaints against CSIS, CSE or the RCMP when technical expertise is required to assess the evidence

The Directorate has 3 employees, as well as a cooperative education student and 2 external researchers. It has also built out links with academic researchers. In the coming year, it will continue to grow the number of employees, support ongoing education, and engage external researchers to build capacity. Curiously, the Directorate also intends to “prioritize unclassified research on a number of topics, including open-source intelligence, advertising technologies and metadata (content versus non-content data).”

Analysis of Technology Directorate

Generally, I am interested in how this Directorate is being developed and the processes that are being established for it to succeed. Specifically, how are external researchers are identified and leveraged? How has the external academic network been (or is being) developed? Answers to these questions could provide lessons for other regulators with different areas of responsibility but which possess (or are building) comparable technology teams.

The specifically stated areas of non-classified research is worth paying attention to. OSINT is a growing focus for national security and has been an area of invite-only meetings amongst Canadian national security practitioners over the past years. The topic area is, also, complicated by some guidance from the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, Treasury Board’s Privacy Implementation Notice 2023-03, and more generally by the United States’ Office of the Director of National Intelligence’s report on Commercially Available Information. This same report may, also, have overlaps with why NSIRA is interested in unclassified work concerning advertising technologies.9

Engagements with Reviewees and Confidence Statements

NSIRA tracks a number of variables that are used to understand the nature of its relationships with reviewed agencies and, also, due to some challenges with particular reviewed agencies has had to develop confidence ratings. These ratings are used to assess how confident NSIRA is in the comprehensiveness and accuracy of the materials it receives from reviewed bodies. The annual report serves to summarise the state of things during 2022.

When discussing engagements with reviewees, NSIRA has adopted a common text-template while, also, adding narrative text that contextualises whether the Agency is experiencing challenges with reviewed bodies. The variables that NSIRA reports on include:

- Access to on-site office space

- Whether lack of on-site access is an issue

- Direct access to network resources or files of reviewed bodies

- Whether there is an issue associated with how access to network resources or files is performed by a reviewed body

- Whether information is produced to NSIRA in a timely manner

- Overall whether the engagements are good, improving, or bad.10

I try to summarise the state of engagements with reviewed bodies in the below table.

| Agency | Office Space | Space Issue? | Network Access | Access Issue? | Timeliness | Good / Improving / Bad |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSIS | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Good |

| CSE | Y | ? | Partial | Y/? | Partial | Improving from bad |

| DND/CAF | Y | N | Y | N | Partial | Good and improving |

| RCMP | Y | N | N | N | Partial | Improving |

| GAC | N | N | N | N | Y | Good |

| CBSA | N | N(?) | N | N | Partial | Good |

NSIRA is now tracking delays when it requests information from reviewed bodies and has a three-part process of sending advisory letters to senior bureaucrats and, ultimately, Ministers when delays persist. Advisory letters were used 5 times in 2022, with 3 having been sent to CSE and 2 to RCMP. There is no explicit indication as to whether these letters were to senior bureaucrats or to the Minister.11

Moreover, NSIRA has expanded the criteria to assess the responsiveness and ability to verify information. These include the following criteria:

- Timeliness of responses to requests for information

- Quality of responses to requests for information

- Access to systems

- Access to people

- Access to facilities

- Professionalism

- Proactiveness

Analysis of Engagements with Reviewees and Confidence Statements

While I appreciate that there may be sensitivities in presenting a table that summarises the nature of NSIRA’s engagements with reviewed agencies, it might be helpful to consider including in the future as more data is accumulated so that NSIRA can provide year-over-year comparisons. Information in this format may be particularly useful to identify areas of improvement for Ministers or their deputies.

NSIRA is, also, clearly trying to mature its confidence statement process. We have moved from what was a ‘tripwire system’ in the 2020 report to a much more robust way to collect, and present, information about the behaviour of reviewed bodies. How this affects confidence statements may be the next step in this maturity process.

Other Items

Complaints Investigations

NSIRA discusses that it is developing processes to more quickly address complaints that it receives. There are two particular calls for law reform around investigations.

- [A]n allowance for NSIRA members to have jurisdiction to complete any complaint investigation files they have begun, even if their appointment term expires.

- Broadened rights of access to individuals and premises of reviewed organizations to enhance verification activities.

Notably, NSIRA is calling for enhanced education–not new powers–with regards to increasing awareness of its mandate around complaints. The Agency writes that,

… members do not have the ability to make remedial orders, such as compensation, or to order a government department to pay damages to complainants. NSIRA continues to make improvements to its public website to raise this awareness and better inform the public and complainants on the investigations mandate and investigative procedures it follows.

Analysis of Complaints Investigations

First, the calls for legislative reform suggest that there has been an issue with a retiring member not being able to complete a file, which added to the transaction costs of handling an investigation, as well as challenges in being able to verify information or activities.

Second, that education and awareness is being called for with regards to members’ abilities and powers, as opposed to calling for new powers, may be indicative of where NSIRA is prioritising its present legislative law reforms. It may, also, speak to NSIRA not wanting to expand its mandate with regards to complaint processes at the present moment in time.

NSIRA Partnerships

NSIRA continues to develop international partnerships and meet with other review bodies, including: the Five Eyes Intelligence Oversight and Review Council, the UK’s Investigatory Powers Commissioner’s Office, Australia’s Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security, the International Intelligence Oversight forum, as well as visiting with the Norwegian Parliamentary Oversight Committee on Intelligence and Security Services, Danish Intelligence Oversight Board, the Netherlands’ Review Committee on the Intelligence and Security Services, and the Swiss Independent Oversight Authority for Intelligence Activities.

NSIRA is also engaging with NSICOP, the Civilian Review and Complaints Commissioner for the RCMP, and the Office of the Intelligence Commissioner, along with legal professionals who are members of other agents of Parliament.

On a technology front, NSIRA has engaged the Privacy Commissioner’s Technology Analysis Directorate, AI technology team at the Treasury Board’s Office of the Chief Information Officer, and the Canadian Digital Service. Finally, the Technology Directorate is specifically identified as responsible for continuing to develop “domestic and international partnerships, including expanding its network with academics, civil society and commercial leaders to ensure key technological issues factor into its approaches.”

Analysis of NSIRA Partnerships

NSIRA is clearly engaging internationally and domestically to learn about, and potentially share, best practices and techniques for engaging with regulated entities. That NSIRA began to host international meetings in the fall of 2023 speaks well to its growing capacity and involvement amongst its peers.

Conclusion

NSIRA has produced another helpful annual report that explains a great deal to the public, and especially to those who have read and assessed many of the annual reports over the years. In particular, the continuing focus on process–how much access NSIRA has to reviewed agencies’ materials, the timeliness of that access, and quality of the engagements–is important should the Government of Canada move forward to consider law reform.

Law reform should, generally, be seen as a last-step measure when it comes to addressing issues between different government agencies. However, should NSIRA continue to suffer challenges in fulfilling its mandate due to lack of access to relevant review materials then changes should likely be considered when the government moves to introduce national security-related law reform.

Footnotes:

- Reviews which have not completed a declassification process, or for which there are no plans to declassify, are not available on NSIRA’s webpage. ↩︎

- Boldface not in original. ↩︎

- Per Public Safety Canada, “Section 12 of the CSIS Act mandates CSIS to collect and analyse intelligence on threats to the security of Canada, and, in relation to those threats, report to, and advise the Government of Canada. These threats are defined in the CSIS Act as espionage or sabotage; foreign influenced activities that are detrimental to the interests of Canada; activities directed toward the threat or use of acts of serious violence; and, activities directed toward undermining the system of government in Canada.” ↩︎

- Per Public Safety Canada, “Section 16 of the CSIS Act authorizes CSIS to collect, within Canada, foreign intelligence relating to the capabilities, intentions or activities of any foreign state or group of foreign states, subject to the restriction that its activities cannot be directed at Canadian citizens, permanent residents, or corporations.” ↩︎

- (Per Public Safety Canada, “Section 21 of the CSIS Act authorizes CSIS to apply for a warrant to conduct activities where there are reasonable grounds to believe that a warrant is required to enable CSIS to investigate a threat to the security of Canada or perform its duties and functions pursuant to Section 16 of the CSIS Act. The CSIS Act requires that the Minister of Public Safety approve warrant applications before they are submitted to the Federal Court.” ↩︎

- Judicial authorisation to retain a Canadian dataset ↩︎

- Emphasis not in original. ↩︎

- For more, see: “Analysis of the Communications Security Establishment Act and Related Provisions in Bill C-59 (An Act respecting national security matters), First Reading (December 18, 2017)“, pages 27-31 ↩︎

- In the United States, Senator Ron Wyden has continued to raise the alarm that commercial advertising and surveillance networks could endanger American national security. I fully expect the same threat to exist to Canadians as well. ↩︎

- Note: on this last item, I am taking liberties in reading between the lines to some extent in how I am categorising the nature of the engagements. NSIRA does not make such a blunt assessment of the status of their engagements. ↩︎

- Given that a meeting did take place between the Minister of National Defence and the Chair of NSIRA, this suggest at least one of the letters to CSE may have been to the Minister. ↩︎